History of the Miami Nation of Indians of Indiana

The Miami Nation of Indians of Indiana is the contemporary national body of the Miami who legally remained in Indiana after removal, which was about half of all Miami people at the time. Today, the Miami Nation of Indiana continues to serve the Miami, hosting language and cultural reclamation events, providing public education on Miami history and culture, managing community-held lands, and consulting with government agencies and public organizations on Indigenous knowledges and perspectives. Our tribe is flourishing, with a tribal enrollment of 2,000 individuals with concentrations of members in Miami, Huntington, Allen, Wabash, Marion, Parke, and St. Joseph counties in Indiana.

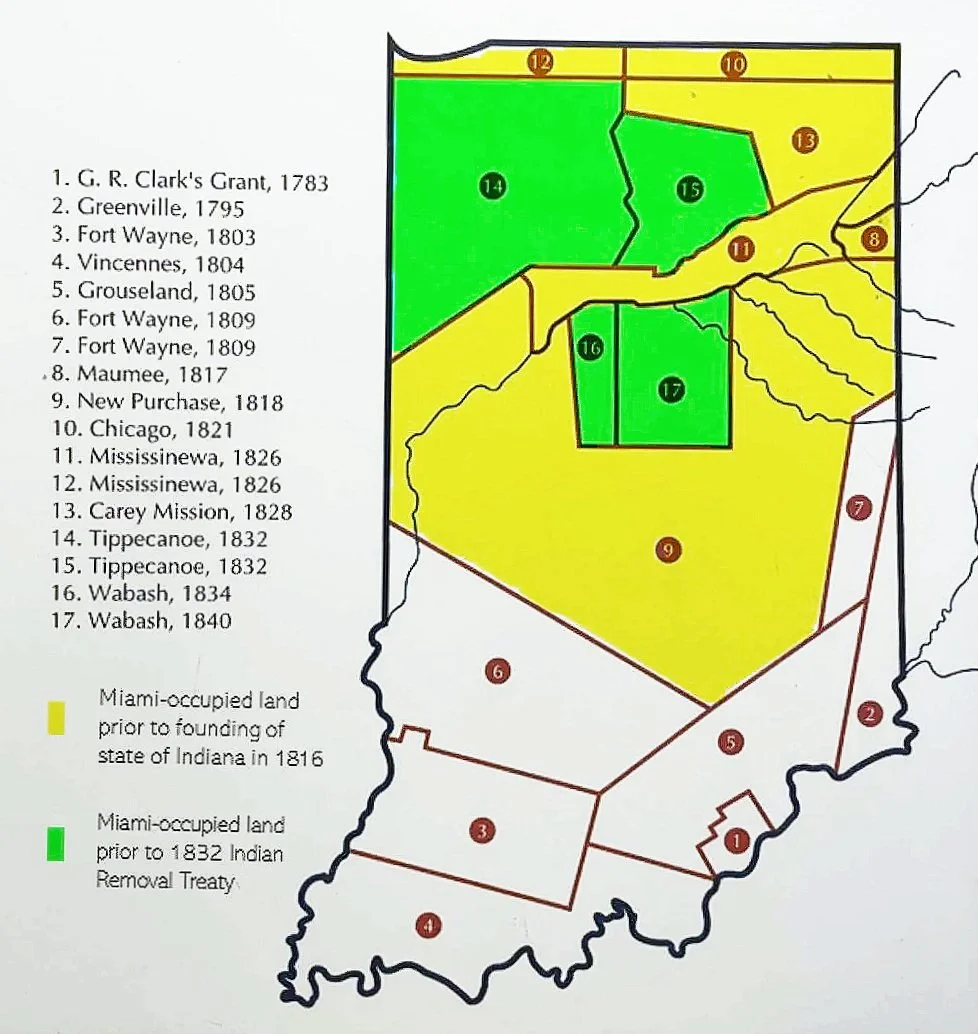

Myaamionki, the Miami homelands, once stretched from western Ohio towards Chicago, south of what is now Indianapolis, and up into Michigan. Before colonization, the Miami regularly traded in what is now Green Bay, Detroit, and Indianapolis. Our corn has been located as far west as what is now New Mexico. At times, we fought alongside Tecumseh and many lower Great Lakes Indigenous peoples have shared history with the Miami in trade and battle.

The Miami retained the majority of their homelands even after the United States declared Indiana a state in 1816, but the US created economic pressures to push for land dispossession and removal treaties. This era was characterized by manipulation, force, and violence. The Miami were able to put off signing a removal treaty much longer than most of the Indigenous nations in the region due to their influence over the waterways in northern Indiana. However, in 1832, Chief Richardville signed a treaty allowing the removal of all Miami except his own family near Fort Wayne. Many Miami did not see this treaty as legitimate because other chiefs were not consulted and did not sign the treaty. Over the next 10 years, the Miami fought the terms of this treaty in every way they could come up with. By the time the US government enacted removal in 1846, nearly half of the Miami were legally granted exemption. These Miami families were deeded treaty land, to be tax-free in perpetuity in Indiana, and given permission to continue to receive their payments from previous treaties at Fort Wayne. This made them the only tribe to be recognized in the State of Indiana post-removal.

The US government forced the other half of the Miami westward to a multi-tribal reserve in Kansas, disrupting their livelihoods by fracturing their relations with Miami lands, foodways, and clan systems. In the early 20th century, the US government moved them again, this time to Oklahoma. Despite this forced separation, the eastern and western Miami people have maintained relationships to the present day.

Treaty Cessions (1783-1840), adapted from Rafert (1999)

Persistence in Indiana

The contemporary Miami Nation of Indiana is made up of the descendants of the Miami who successfully fought to remain in Indiana before 1846 and have been fighting to retain their lands and rights as Indigenous people in Indiana ever since. Remaining in Miami homelands allowed the eastern Miami to thrive, greatly increasing their number in the following decades. However, they faced constant encroachment and lumber theft by settlers and struggled to gain legal protection because the Miami and other American Indians of this time were not US citizens and thus could not bring legal cases forward on their own.

In the 1890s, the State of Indiana illegally charged back taxes on Miami treaty lands and then confiscated the land for payment, even arresting Miami heads-of-households for non-payment. In the early 20th century, the Miami fought heavily to regain those lands and maintain spear-fishing rights. In the 1940s, the Miami began fighting against the flooding of those treaty lands by the State of Indiana. These lands later became the Mississinewa Dam and Reservoir.

From the 1950s to the 1970s, the Miami were deeply engaged in establishing their rights with the US government. This included collaborating with the Indian Claims Commission, reaffirming the illegality of taking Miami lands in the 1890s. In addition, tribal members launched several legal cases, including one that successfully required state and local governments to repay taxes that were illegally levied. In 1978, the Miami of Indiana initiated a formal petition for federal recognition through the US Department of the Interior’s newly established Office of Federal Acknowledgment. This complex case and its appeals continued through 2003, requiring vast resources and the collective efforts of the Miami community and leadership.

In July of 2004, Chief Brian Buchanan and Vice Chief John Dunnagan were invited to the United Nations to address the Commission on Human Rights, Sub Committee on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights Working Group on Indigenous Populations. During his remarks to the Committee, Chief Buchanan advocated for Miami sovereignty and called for the United States government to implement the UN’s Draft Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (later adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2007).

In 2009, many Miami Nation of Indiana citizens received settlements from the Cobell v. Salazar class-action lawsuit. At the time, this was the largest class action lawsuit ever brought against the US government, with a payout of $3.4 billion in December 2010. This case sought to remedy the mismanagement of funds held by the US government on behalf of American Indian peoples across the country. In the case of the Indiana Miami, the US government was holding in trust the compensation owed to Miami people for the theft of their lands in the 1890s. Each Indiana Miami who received settlements was paid between $800–$2,000 for this injustice.

Today, many members of the Miami Nation of Indiana are considered “adult American Indians” under the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). This means that most Miami have BIA payroll numbers, were named in the Cobell settlement, and are recognized as individual American Indians under US law. However, the Miami Nation of Indiana is not currently recognized as a sovereign Indigenous nation by the US federal government. It is one of the many odd inconsistencies in US-Indigenous relations created when policy is crafted on a nation-by-nation process.

Federal recognition efforts are still ongoing. Tribal officials are working at the state, national, and international levels to maintain our role as a consulting body over Miami lands, ancestral remains, and to regain our status as a treaty-signing body with the US government. Although the Indiana Miami have always maintained their own government and membership, sovereignty (federal recognition) would allow us to be considered an independent nation with the ability to adjudicate legal cases, levy taxes within our borders, and possess greater control over our economic development.

Miami Reunion (2025). Annual Miami Nation of Indiana Gathering

Peru Circus Parade Float (2023). Banners affirming “Made here, Stayed here, Still here” and “Indiana Land of the Miami” adorn the float alongside banners of turtles and cranes.

Culture

Miami are lower Great Lakes woodland people. Historically, the Miami lived in wigwams, wore center-seam moccasins and winged ribbonwork leggings or blanket skirts decorated with porcupine quills, and, later, silk ribbons and trade silver. Miami villages were located near rivers and bodies of water that connected them through canoe culture. The Miami hunted and fished and were known as farmers. The Miami white five-kernel corn was valued for being both sweet and hardy, making it suitable for storage over long winters. The historical Miami clan system created and produced reciprocity, interconnectedness, and resilience.

The Miami speak Myaamia, an Algonquian language, which is the largest family of Indigenous languages in North America. People who speak one of the many Algonquian languages share many socio-political and cultural characteristics. For instance, many Algonquian language communities play similar games, such as lacrosse, the plum stone (or bowl) game, and the moccasin game. Algonquian communities also share similar yet different stories. Some Miami stories are only told during certain times of the year and have passed through oral traditions.

The Miami may say niila myaamia, or I am Miami; however, regional Indigenous peoples often refer to the Miami as the crane or sandhill crane people. Sarah (Siders) Bitzel, the tribal secretary, tells the story of how this came to be:

We were in a battle with a group of Cherokee warriors who chased us into a wooded area. The Cherokee ran into the woods to attack because they thought it would be easy. They searched everywhere.

“Where did they go?” the Cherokee wondered. Some of the Cherokee suddenly heard the whooping sound of the crane. Then, “cranes” swooped down from the trees and defeated them in battle.

We are a woodland People, we know how to navigate in the forest, in the trees. Their belief is that we shape-shifted. Did we? Who is to say? A few survivors went back to the Cherokee and told them the story, adding “they have the power of the crane on their side.”

Today, the Miami of Indiana continues to practice and pass on cultural traditions through community events and youth programs. There are several community drums that regularly practice Miami songs and drumming. Women often dance, sing, and make regalia for community events. Contemporary artists studying historical art are reviving creative practices and design. There is also an annual summer camp for Miami youth to connect with culture and build lifelong relationships. The Miami Nation of Indiana offers language programs for youth and adults.

The contemporary Miami language, Myaamia, is distinct from the Miami language found in older historical documents and the Miami spoken by Indiana Miami in the mid-twentieth century. The contemporary Myaamia programs developed in the 1990s from the close relationships between Chief Frances Dunnagan of the Miami Nation of Indiana and Chief Leonard of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma. They signed a language pact that would draw on the language resources that continue to exist among the Indiana Miami and funding and staff resources available to the Oklahoma Miami as a federally recognized tribe to develop language programs and resources to be shared by all Miami. Through this pact, which helped fund the work of linguist Dr. David Costa, emerged a Myaamia-French dictionary, a Myaamia-English dictionary, language camps in both Indiana and Oklahoma, and the earliest Myaamia phrase books and children’s curriculum.